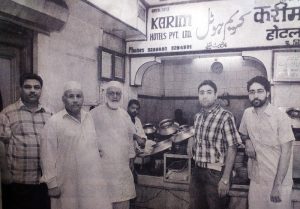

DELHI’S FIRST FAMILY OF MUGHLAI CUISINE, THE OWNERS OF KARIM’S, HAVE TRADITIONAL TASTES AT HOME AND AT WORK

The building in a narrow, sunless alley just off he imposing bulk of the Jama Masjid is just like any other in the neighbourhood. There’s nothing — absolutely nothing — to mark it as one of the landmarks on Delhi’s gastronomic map. although this is where the owning family of Karim’s lives.

Karim’s was started in the year of the Delhi Darbar of 1911 by a descendant of the cooks of the Mughal court. Haji Karimuddin. It started off as a street-side cart that catered to travellers, for, at that time, visiting restaurants as a lifestyle statement was still decades away. The cart, in those days of super-specialisation, sold two items: dal and aloo gosht. Both dishes were too homely to be true, and diametrically opposed on the food spectrum to what Haji Karimuddin’s ancestors cooked for the Mughal court.

In the fullness of time, Haji Karimuddin had one son. Nooruddin, who in turn had four sons of his own — Zahooruddin, Sharfuddin, Alimuddin Ahmed and Salauddin. It is these four brothers, now in their seventies, who form the old guard of Karim’s today. Between them, they have 11 sons (plus daughters, but they’re not part of the family business, and my conversation is about business, isn’t it?). Some of these sons have opened outlets under the same name, -Karim’s”, but they are not really branches.

I gently rib the Haji about whether his future daughter-in-law — son Zainuddin is engaged to be married to a girl from Ballimaran — is busy honing her cooking skills to match those of her famous in-laws. The family burst into peals of laughter: this is not an aspect that they had considered before. Haji Alimuddin denies that their home food is any different from what the neighbours eat — after all, Karim’s is run by mere men, whereas at home it is the women who do the cooking, and everyone knows how much more superior a woman’s hand is in the kitchen. “Like everyone else, we eat dal, the occasional vegetable, or meat with vegetables or dal cooked together, or matar pulao.” Occasionally, the ladies of the house order something from the restaurant, and even more occasionally, the family goes out to eat, favourite places being Dum Pukht and Masala Art at the Taj Palace hotel.

The family behind the famous Karim’s at Jama Masjid denies that their home food is any different from what the neighbours eat —after all, they say, Karim’s is run by mere men, whereas at home it is the women who do the cooking, and everyone knows how much more superior a woman’s hand is in the kitchen

That the family is very traditional can be seen from their cuisine, which has not changed since the restaurant began operations in its present avatar. No ladies of the family work outside the home, whether daughters or daughters-in-law. And though foreign travel is not a novelty- Malaysia, Dubai, the UK and Saudi Arabia (for Hajj)- they have never felt the need to expand operations overseas. “God has given us success here. Where is the need to spread like wildfire?”

There are a couple of other factors in their success. The first is that Karim’s has stuck to its core competence, refusing to bow to popular demand. No tacked-on Chinese dishes and little vegetarian food, because that is not the way this particular cuisine works. The second is that the surroundings of Jama Masjid is a catchment area for those who regularly eat this food. They know their istew from their qorma and would not dream of urging the management to cook with less oil. The core customer is happy to eat mutton and chicken daily, and scoop up gravy with rotis made from a mixture of maida and atta.

The other factor is that Karim’s has never had any competition. Delhi Muslim cookery begins with precise butchery and many renowned chefs started out their life as butchers — but most of them are employees, not employers. This family is the only known instance of royal cooks continuing an age-old tradition in settings that attract international travellers and upper-class Indians. And one thing is for sure: without business savvy, Karim’s would have been a tottering empire resting on its past glory. Paying electricity bills and replacing staff uniforms may not be as critical as blending spices, but it is vital to the health of a restaurant.

The old family home in Gali Kababiyan, just behind Karim’s, Jama Masjid, could well be a metaphor for the family it houses: it gives away no secrets. Though Karim’s has been featured in every major publication including Time magazine, its owners are a supremely low-key bunch. A couple of years ago, when Karim’s received an award for its cuisine from a local publication at a public function, the prize was a bottle of wine. Did the extremely pious Haji let the organisers know that wine was as out of place in his life as a heater in the Sahara desert? Certainly not. He received it with appropriate gravitas, never letting the organisers know how incongruous it was to present a haji with wine.

Though every male member of the family knows how to cook their way through the entire menu, the real secret of the phenomenon called Karim’s lies elsewhere: the blessing of god.