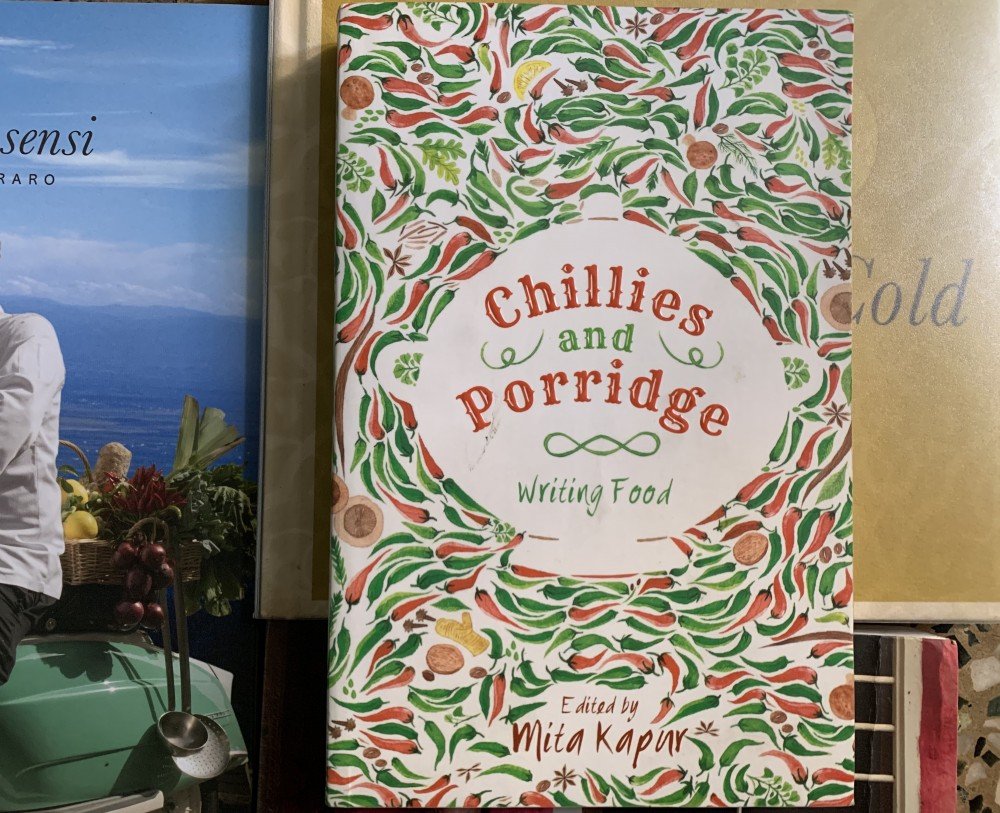

What is the first thing that you think of when the word ‘food’ is mentioned? Your mother’s cooking, the gourmet delights  of travelling, five star dining, street food, the ghastly fare dished up by your office canteen-wala or all of the above? This remarkable volume, Chillies and Porridge, Writing Food, edited by Mita Kapur, published by Harper Collins (pp 272) has managed to encapsulate an impressive amount of food from across the spectrum. The only way to have gone about it is was to have asked a variety of people to contribute, in order to involve the widest possible cross-section of perspectives. Thus, we have journalists, wildlife professionals, chefs, fashion designers, food historians, television stars and authors. The editor, Mita Kapur, has been careful to give voice to as many different points of view as possible and some of these have been a complete joy, and the backbone of the book.

of travelling, five star dining, street food, the ghastly fare dished up by your office canteen-wala or all of the above? This remarkable volume, Chillies and Porridge, Writing Food, edited by Mita Kapur, published by Harper Collins (pp 272) has managed to encapsulate an impressive amount of food from across the spectrum. The only way to have gone about it is was to have asked a variety of people to contribute, in order to involve the widest possible cross-section of perspectives. Thus, we have journalists, wildlife professionals, chefs, fashion designers, food historians, television stars and authors. The editor, Mita Kapur, has been careful to give voice to as many different points of view as possible and some of these have been a complete joy, and the backbone of the book.

Two stories are, in my opinion, the best in the book. One is by two well-known television food show hosts, Rocky Singh and Mayur Sharma. Both are army kids, and both have been close friends of each other for decades. Though I have followed their TV programmes off and on, it was a revelation to see just how well they can write a story. First of all, they have attempted to do so in two parts: one in Singh’s rambunctious voice and the other in the far gentler voice of Sharma. It is an idea that can either work exceedingly well or flop badly. Their narrative is a memoir of army life in the 1980s, in cantonment towns when playing cricket in the maidan and eating simple comfort food in each other’s homes were highlights. It is impossible to read it without a sense of nostalgia for a more elemental time when childhood was about playing under an open sky rather than yearning for X-boxes and iPhones!

The other is by Srinath Perur and deals with a topic that is becoming relevant to the point of frenzy these days: vegetarianism. It is difficult for a vegetarian to talk about meat – or indeed vice versa – without a certain degree of revulsion, but what Perur has achieved in this chapter with cool, dispassionate analysis, deserves applause, more so in these polarized times. The best part is that he did not appear to be writing about food per se, but a social trend, which lent weight to his words.

The other compelling piece is by Nilanjana S Roy, who attempts a rather unusual angle: that of “the other kind of street food, so everyday that it barely registered to the Indian eye and that most food writers and historians didn’t consider worth noting”. Ragi or millet, according to Roy, is a partially unseen sub-text of food in India, which has been overshadowed by rice and wheat, both largely eaten in their milled state, unlike millet, that is eaten as a whole grain. It is the same for meat and even vegetables. Prime cuts of mutton and chicken are sold to upper middle-class households from vendors who stop by at the front door of the house, whereas similar vendors who come calling at the back door usually sell pork and beef for the domestic help. With Roy’s skilled prose, we can see how foraged vegetables which had lost favour, are now coming back at least for the expatriate community.

The other compelling piece is by Nilanjana S Roy, who attempts a rather unusual angle: that of “the other kind of street food, so everyday that it barely registered to the Indian eye and that most food writers and historians didn’t consider worth noting”. Ragi or millet, according to Roy, is a partially unseen sub-text of food in India, which has been overshadowed by rice and wheat, both largely eaten in their milled state, unlike millet, that is eaten as a whole grain. It is the same for meat and even vegetables. Prime cuts of mutton and chicken are sold to upper middle-class households from vendors who stop by at the front door of the house, whereas similar vendors who come calling at the back door usually sell pork and beef for the domestic help. With Roy’s skilled prose, we can see how foraged vegetables which had lost favour, are now coming back at least for the expatriate community.

Food is not just about the feel-good factor, so abundantly available in hotels and restaurants across the country. It is also about the sheer convenience of a slum-dweller feeding her school going children with Maggi noodles and potato chips for the same price as dal and vegetables. Tara Deshpande Tennenbaum’s rather foreboding piece is an ominous warning for public health in the country if we continue to consume refined food.

Sidin Vadukut’s amusing take on a Prime Ministerial banquet menu packed in a few howlers, such as calling gramflour ‘chickpea flower’ and the chefs – Manu Chandra and Floyd Cardoz hadn’t, apparently been given a brief, except to “write something about food”. If there is one flaw in an otherwise interesting book, it is the lack of sub-editing.