Exploring Srinagar is largely a matter of personal choice: the delight of a shikara is its stately, unhurried pace; a cycle ride around is the perfect answer for seeing what you want. Stop every ten feet to take the perfect shot without disturbing anybody, travel by yourself if you are a loner, or with a dozen others if you’re not, and have an outrageously good time!

Chief of Srinagar’s delights is its exquisite beauty which delights both the first time visitor and the seasoned traveller alike. However, what makes the city so special is the wealth of things to see whether it’s your first visit or your tenth. Many of us accept, however, without question what lies before our eyes, visiting only the best known of Srinagar’s splendours and leaving the rest unexplored.

This is not a guide in the conventional sense of the word: it does not list ‘famous sights’ in order of importance. Neither does it compel you to make long trips to out-of-the-way places. Every subject touched upon in these pages lies within the city of Srinagar and is, more or less, what you would see anyway.

How to explore Srinagar is largely a matter of personal choice. While you will definitely want to explore the city’s waterways — Dal Lake, Nagin Lake and River Jhelum — by shikara, you can explore the Mughal Gardens, parts of the Old City and Hazratbal Mosque also by shikara. This should take you a whole day: the delight of a shikara is its stately, unhurried pace. On the other hand, you can take a shikara only for the waterways and a taxi is a little too ‘sealed’ for many tastes, and after all, how many times can you ask the driver to stop on the way for the perfect shot? If this is your problem, a cycle ride around the city is the perfect answer. See what you want, stop every ten feet to take the perfect shot without disturbing anybody, travel by yourself if you are a loner, or with a dozen others if you’re not, and have an outrageously good time!

Dal and Nagin lakes

What makes these lakes so special is that they’re an integral part of the city, and also that far from being conventional flat bodies of water, wide tracts of them have villages, lotus gardens and vegetable gardens!

A large proportion of the lakes are owned by individuals. While some families own only the piece of water on which their houseboat stands, others own whole acres. These are put to good financial use by growing crops of lotus on them. The lotus root is a highly prized vegetable all over north India, and not surprisingly, Srinagar produces some of the country’s best. Each `plot’, zealously guarded by the owning family, is separated from the neighbouring plot by a thin trail of water, just wide enough to allow a narrow boat to pass, aiding the collection of lotus roots. While the flower blooms in July-August, the vegetable matures in autumn.

Water chestnuts or singhara also grow wild on the lakes. Connoisseurs claim that while the best water chestnuts come from the Wular Lake, those that grow in certain stretches on the Dal compare very favourably. Lightly roasted in their jackets, singharas are sold as snacks, by the side of the road.

Every visitor is offered a shikara ride to, among other places, the vegetable gardens. Nowhere in the world is the dictum ‘necessity is the mother of invention’ taken so literally as here! Family owned plots of water have been converted into ingenious vegetable gardens. Here’s how: weed is collected as fertilizer, dried in a compost heap and mixed with salt from the lake. Twigs of trees are tied together to form the base over which compost is spread. By this simple expedient, ‘land’ is formed, extremely rich in plant nutrients. It is kept moist by the water that surrounds it, and because of its lightness, floats on the surface no matter what the level of the lake. Tomatoes, cucumbers, melons, turnips, carrots , whatever grows on ‘land’ also grows on the lake, with a bountiful yield and excellent quality.

During a shikara ride, you may see boats laden with vegetables being rowed along. These vegetables have just been picked and await the next day’s vegetable market,

Every morning, at the crack of dawn, at least one hundred boats gather at a clearing in the interior of the Dal. Known to all shikara and houseboat men quite simply as ‘the vegetable market’, buying and selling by the hundred-weight takes places briskly.

Tourists in shikaras — and there are dozens — are expected to watch from the wings, as space is at a premium. There’s just enough for the sellers and buyers to maneouvre their boats which are packed tightly together, the trader perched on the tip of the prow. By the time dawn’s colours have changed from amethyst to dusky blue and then pink, business is over and there is time for a chat over the ever present hookah. Two local equivalents of snack bars arrive every morning to catch the crowd. One shikara sells an unleavened bread spread with a spicy mixture, but there are quite as many takers for Mohiuddin’s halwa. Fluffy stewed semolina is kept steaming hot on a burner in the boat itself. Piled high on flat buns, halwa made and sold on a boat in the middle of the lake at dawn is highly recommended as a worthy compensation for waking up at 5 am!

From the vegetable market, buyers trundle their boats either to the Boulevard or to Ashai Bagh Bridge where horse drawn carts await them. Laden with vegetables, these make their way to wholesale vegetable depots in the city, and even to other towns in Kashmir.

One sight, typical of Srinagar is that of a lone woman in a boat plucking leaves from the lake. There are two types of leaves — one is that of the waterlily which provides cattle fodder. Yes, a few cattle too inhabit villages on the lake! The other sort of vegetation occurs in open areas of the rakes and dried, provides valuable fertilizer for vegetable gardens.

A typical sight during your shikara ride- lotus blooms from floating gardens where they are grown as a commercial crop.

Little is allowed to go waste in the tightly woven economy of Srinagar’s lakes. Even the weeds that cling to the bed of the lakes and have to be extracted by machine provide fertilizer, however evil smelling!

Bulrushes that grow wild, have their uses too. Cut, then left to dry, they are made into rush matting which is always in demand throughout Kashmir as floor coverings. Weaving wagguh as these straw mats are called, has been an age-old tradition on the lakes. The women who weave and sell them augment the family income. In the great Friday bazaar at Hazratbal mosque, you may see a wagguh seller or two.

You may also see, at the same bazaar, a row of women selling fresh fish, dried fish or stalls selling batter fried fish. When compared to rainbow trout, ‘Koshur gad’, small and flat bodied, and a type of carp, doesn’t stand a chance, but it is native to the waters of Srinagar’s lakes unlike trout which was introduced to Kashmir by the British at the turn of the century. It is caught by fishermen who cast nets into the water. This is quite an art, and like that of skilfully manoeuvring boats, this trick lies in nifty wrist work. Weights are attached to the ends of a net, and with a deft movement the net unfurls like an umbrella and sinks into the water. Long practice determines when it is ready to be closed with a twitch of rope, and pulled into the boat, full of shimmering, wriggling fish.

A large portion of the city’s fisher folk live in Telbal, a picturesque village past Shalimar gardens on the banks of the lake, and the waters off Telbal provide a year round fishing ground. Traditionally, men catch the fish and women sell them in markets. If you pass Telbal by car, notice the enormous chinar tree that serves as the local bus shelter. It is said to be the largest and the oldest in Srinagar.

Architectural features

Boats

Few writers mention boat building as a craft when discussing Kashmir’s crafts. Shawl embroidering, papier mache painting and carpet weaving certainly address themselves more directly to the buyer, but kishtis, doongas, bahats and the houseboat are a vivid testimony to the skill of those who build them.

Abul Fazl, the author of the ‘Ain- i-Akbari’ , records in about 1590 (when Akbar, the Mughal emperor made his first visit to Kashmir) that boats were the centre upon which all commerce moved. Not surprisingly, in the absence, then, of good roads and modern vehicular traffic. Timber and grain were regularly transported to Srinagar, the centre of trade in Kashmir, by boat. So were passengers. Passenger boats still carry people to villages on the Dal after Friday prayers at Hazratbal.

The wood of the deodar tree is always used in boat building. It seems to be more durable for its purpose than any other wood.

The intricate carving on the balconies of most houseboats testify to the skill of the craftsmen. Khatamband work on the ceiling adorns most houseboats. Made of thin strips of pine wood, cut into various geometric forms, and held together by an intricate system of grooves, khatamband is a special carpentry technique practised by a community called khatamband chans or carpenters. Khatamband is not restricted only to house-boats — every old house has this work on the ceilings in various geometrical designs — hexagons, pentagons or octagons are interlinked to form other geometric designs.

Khatamband is a craft which conforms to the Islamic nature of Kashmir, and was probably introduced there during or after the 14th century. Islam does not encourage the drawing or sculpting of human likenesses and, as a result, Islamic art has tended to become characterised by extremely advanced calligraphy and the highly sophisticated use of geometric figures. And that is precisely what khatamband is. It is used in other Islamic countries of North Africa, Central Asia and Iran. Srinagar’s finest example of khatamband is the shrine of Naqshband Sahib in the Old City, just past Khanyar.

Shrines

Naqshband Sahib is one of Srinagar’s many shrines. Others dot the whole city. The architecture of shrines and mosques in Kashmir is distinctive. Here, but for the new shrine of Hazratbal, there is no dome — quite unique in the Islamic world! Perhaps the reason lay in the availability of raw material, or perhaps in the skill of the artisans who could work with wood but not with other materials. Islam was brought to Kashmir by a Persian mystic, Mir Sayyid Ali Shah of Hamdan in the 13th century. Before that time, Kashmir’s population was Hindu. It is curious that Shahi Hamdan, as he is called, did not attempt to re-create domed mosques with minarets in Kashmir. What is even more inexplicable is the failure of the three Mughal emperors who visited Kashmir — Akbar, Jehangir and Shah Jehan — to build even one fine mosque in the Mughal style.

The Mughal connection

Kashmir became a part of the Mughal empire in 1586 under Emperor Akbar. He travelled to Kashmir three times and laid out the Nissim Bagh near Hazratbal shrine . Out of the 1,200 chinar trees that he planted, some still stand. Nissim Bagh, which translates as the ‘garden of breezes’ is now in the compound of Kashmir University.

Emperor Akbar also built, in 1590, the wall around the Hari Parbat Hill. In 1590, Kashmir was reeling under a severe famine and the fort was built to generate employment. It is pierced by two large doorways — the Kathi Darwaza in Rainawari, and the Singeen Darwaza in Haval. The Kathi Darwaza bears a Persian inscription about the date of commencement of the wall. A lesser doorway leads up to Makhdoom Sahib, another shrine.

Emperor Akbar had constructed a township within the Hari Parbat wall. Alas, nothing at all remains of this.

The fort atop this hill was built in the 18th century by Atta Mohammad Khan, an Afghan governor. The outer walls are in a good state of repair but the inside is in ruins. Permission to enter the fort must be sought from the Archaeological Survey of India whose office is in Lal Mandi.

Akbar was succeeded to the throne by his son Jehangir, who loved Kashmir with a passion that was more intense that his father’s. Jehangir laid out the Shalimar gardens; his empress, Nur Jehan built the Patthar Masjid on the banks of the River Jhelum. This is one of the very few mosques in Srinagar to have been built of stone.

Jehangir’s son, Emperor Shah Jehan was responsible for Cheshma Shahi, one of the Mughal gardens, but not much else. His son, Dara Shikoh, however, has left his signature in Srinagar. Pari Mahal, the delightful `fairy garden'”above Cheshma Shahi, was built for his Sufi Teacher, Akhund Mulla Shah. Lovely and largely unvisited is the mosque that Dara Shikoh built for Akhund Mulla Shah. It lies by the steps leading to Makhdoom Sahib, and is built, like Pathar Masjid, of stone. There is only one other stone mosque in Srinagar: that of Madin Sahib, in Haval.

Architectural enigma

Few can explain the absence of domes in Srinagar. It is not as if the structure was completely unknown. One of the architectural curiosities of the Old City is of red brick topped by five domes. This is the tomb of Zain ul Abidin’s mother, known to all and sundry in Srinagar as ‘Budshah’. Just a short walk from Naina Kadal, the fourth bridge, it is not on any tourist map, and if steps to ensure its preservation are not taken, may crumble into ruin. No information about this structure exists. According to some, it was a Hindu temple, but if this is so, it certainly is unique in its design. But then, if it was built as a mausoleum by Kashmir’s much loved king, Zain ul Abidin (1420-70) for his mother it is still unique, for there are no other domed structures in Srinagar, and one built of red brick.

This architectural enigma is called Budshah because that was the title given to Zain ul Abidin, the king who is responsible for promoting handicrafts in Kashmir. He invited wood carvers, embroiderers, carpet weavers and papier mache painters to Kashmir mainly from Iran, and from being once the preserve of only a handful of families, a very large portion of Kashmir’s population is today engaged in handicraft production. This ranges from a few families who trace their ancestry back to Iran, whose minimal output becomes collector’s items, to mass produced items when the emphasis is on quantity.

Till today, areas in Srinagar are associated with certain crafts and not others. Most numdha rugs are still made in Gojwara in the Old City. On a sunny day, you’ll find hundreds of them drying at the foot of Hari Parbat Hill.

If you’ve got time for just one or two shrines, Shah-i-Hamdan on the banks of the Jhelum is a powerful testament of the sophisticated techniques practised by Kashmir’s wood workers. It is right in the old city and can be explored along with the rest of its surroundings.

Hazratbal shrine is Srinagar’s newest mosque, complete with dome and minaret. It enshrines a hair of the Prophet Mohammad and is visited by thousands of devotees every Friday afternoon. A colourful bazaar springs up from noon to 3 pm every Friday making it the best time for a visit to Hazratbal.

Traditional Houses

Quite apart from religious architecture, some old houses in Srinagar make use of ornate embelishments on their exterior. A group of three houses below Makhdoom Sahib is decorated with glazed tiles and ornamental brick work. Houses in Zadibal are noted for ornate lattice windows. Zadibal is to papier mache what Gojwara is to namdhas. Even the Imambara close by, destroyed and rebuilt several times, contains beautiful papier mache work are on the ceiling.

if you’re going for a shikara ride near Rainawari, the houses there too have interesting features- projecting wooden balconies, fancy brickwork and steps leading down to the river to facilitate washing clothes!

Typically, houses in Srinagar are built of buff coloured brick or stone supported by wooden beams. At one time, thatched roofs were the norm today, after the advent of corrugated sheets, they are very much the exception.

Bridges

Seven wooden bridges span the River Jhelum. Although none of the original ones remain, those existing have all been constructed in the traditional, time-tested manner of sinking boats laden with stones to form the foundation. Like houseboats and doongas, bridges are built of deodar wood. The first bridge ever to be constructed over the Jhelum was Zaina Kadal, by King Zain ul Abidin. Nobody knows how pedestrians crossed the river before the rule of the good king!

The seven bridges — Amira Kadal, Habba Kadal, Fateh Kadal, Zaina Kadal, Ali Kadal, Nawa Kadal and Saffa Kadal — are those over the River Jhelum. However, the charm of the Old City is its intricate waterways spanned by smaller bridges, each bearing the same style of construction. The only exception is an old Mughal stone bridge in Rainawari.

Saffa Kadal was, till the turn of the century, considered the most important bridge, because there was none other for twenty miles downstream. Central Asian traders from Yarkand and Ladakh were, even in the early years of the present century, a common sight. Dressed in flowing robes of many colours, accompanied by yaks bearing loads of rugs and china bowls, the traders would spend the night at the Yarkandi Sarai at Saffa Kadal, and the yaks would be sent to graze in the nearby Idgah. Today the Yarkandi Sarai still stands: it houses a resident population of families from Ladakh, but gone are the Central Asian traders and their yaks.

Close to Saffa Kadal in importance was Maharaj Gunj near Zaina Kadal. It was the prime centre of trade, and from the written accounts we have of travellers in the last century, Maharaj Gunj appears to have been full of handicraft shops. Now, of course, no handicraft shops remain, and the road looks like any other in the Old City. It still retains a trace of its former prestige in the wholesale spice shops.

If you want to visit the Old City but don’t know where to start, look around Zaina Kadal. It has everything that Srinagar’s Old City offers. Not far away are Patthar Masjid and the shrine of Shahi Hamdan. Just off the bridge is the tomb of Budshah. You’ll see fine old houses — there’s a particularly ornate one just by the Budshah tomb. And then, there are shops! While they don’t have anything of particular value for the tourist, they are colourful and interesting, and worth a look anyhow. There are a few shops selling copper utensils: china plates and serving dishes are not in use in Kashmir. Instead, every utensil is made of copper and plated with tin. Often, copper vessels have very delicate low-relief work on them. Every copper-ware shop has a piece of yellow paper prominently displayed. Copper-ware is sold by weight, and the yellow paper indicates the prevailing rate. Also in the same area are shops selling skeins of silk and woollen threads. Examine the colours carefully — they are all chemically dyed, vegetable dyes not having been in use for a hundred years now. However, there is a muted, earthy quality to the colours which is uniquely Kashmiri. They are the colours of the Kashmiri carpet, quite unmistakeable from those of any other Indian carpets.

Zaina Kadal’s shops sell an exotic mix of merchandise that range from Pakistani salt to prayer caps.

Getting around

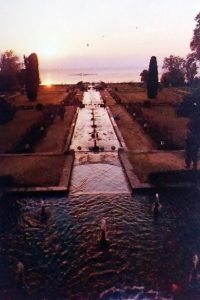

Set aside one day for exploring the Dal and Nagin lakes. The trip could include a visit to the Mughal Gardens. Evening is the best time to visit them. It could also include a visit to Hazratbal mosque, as by far the best view of the mosque is from the lake.

You can explore the Old City by shikara, or alternatively by cycle. For the first timer, all roads and bridges look the same. So unless you have a good sense of direction, it’s best to hire a taxi. If you’re on your own, you can spend as little as one hour in the Old City. If you have a guide to explain all the exotic sights to you, it will take you far longer.

All mosques and shrines are open to everybody, including tourists. However, shoes must he taken oft at the door — there’s usually somebody to mind them. The keyword is to look inconspicuous — in matters of dress, and by not walking around when everyone else is praying. Women and non-Muslim men are not allowed beyond a certain point in shrines: and in both mosques and shrines, bare shoulders and knees are not looked upon with favour.

Do you want to know anything else? About Kashmiri culture or information about any of the less wellknown places to visit in Sringar? Contact the Information Counter at the Tourist Reception Centre, Srinagar.